Montessori and the Acceptance of Holism

By Chloe Burns, Tallgrass Network youth outreach coordinator

One of the most frequent questions people have about Holistic Management is: "How do we get people to accept a new way of thinking?"

This question is still hard for me to wrap my head around, because I never had a problem understanding the paradigm. In fact, it would've made less sense to me to try and adapt the conventional, monocultural way of growing food. Part of this is because I was 17 when I was introduced to HM, and therefore I didn't have decades to be set in my ways. But I think another part can be attributed to my early Montessori education.

My first time seeing Allan Savory's Holistic Management in use in Zimbabwe, 2014.

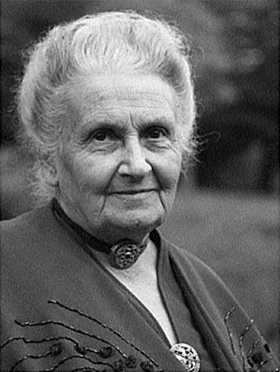

Maria Montessori, 1870-1952.

Like Allan Savory, Maria Montessori was far ahead of her time in her thinking. She was born in Italy, 1870, and took a quick liking to science and mathematics. At 13, she entered an all-boys technical institute to prepare for a career in engineering. However, she then chose a new focus, and graduated from medical school in 1896, becoming one of Italy's first female physicians. With a specialty in psychology and educational theory, she quickly began to question the ways children were being formally taught. She began to observe children with intellectual and developmental disabilities, and was soon made a co-director of a training institute for special education teachers. The program was quickly deemed a success.

In 1907, Montessori went on to open a childcare facility in a lower-income district of the inner-city, given this privilege because the children were simply wanted off the streets. She found that the children were unruly in the beginning, but looking for something to do, they quickly showed interest in working with puzzles, learning to prepare meals, and manipulating mathematical materials. What she found was that they began to teach themselves. Much like a natural ecosystem, with enough structure and without a heavy hand, they flourished beyond what was expected.

Fast forward approximately a hundred years, and I was being sent off to my own Montessori elementary school. I didn't actually realize my school experience was different from traditionally educated until about the third grade, when I had a discussion with a student from a nearby public school:

"I'm so excited for summer," he said. "I hate school!"

"You do?" I asked. "Why?"

He gave me a look of utter disbelief. "You like school?" And then he scoffed. "Goody two-shoes!"

Re-visiting my Montessori elementary school for my brother's Thanksgiving Feast, where the kids do all the cooking, 2012.

To be fair, this is probably an exaggerated, overly-simplified, movie version of what happened. But the effect was the same; I learned that disliking school was the norm. I didn't understand this, because school was the best part of my day. I got to go in, see my friends, sit down with a pile of books, and write report after report on all manner of subjects: Egyptian religion and burial practices, atmospheric conditions of Jupiter, the War of 1812. Even the things I wouldn't have chosen to do on my own, I didn't mind, like learning cube roots or cleaning the kitchen after lunch.

Going to school meant more than getting a stripped-down version of information; it meant going into my community and engaging with it. To do anything else seemed insane and, for lack of a better term, empty.

And when I transferred to public school in seventh grade, that's exactly what I felt. I felt my community stripped away, my information spoon-fed to me, and my responsibilities and independence vanish. In trying to micro-manage for a specific result -- that being to score well on standardized testing -- it seemed that the public school system was losing more than they realized could exist in the first place.

My at-home graduation after taking my GED at 16, in 2013.

So when I was introduced to Allan Savory and his method of managing nature in wholes, I felt like I was finally coming back to something I could understand. By this time, I had left public school early, because while I was scoring well on tests, my entire quality of life was suffering. Without challenge, I was bored. Without a community, I was alone. And the school, in its attempts to fix these problems, seemed to drive them deeper. So I picked up my things and went to college instead, giving me the freedom to dive headfirst into the adventure that our family was about to begin.

What I found was an incredible list of parallels between Montessori and Savory:

- Both methods manage for complexity. Just as Savory had realized that all of nature exists in endless loops and cycles of inter-connectivity, Montessori found that children could not truly absorb information by sitting still and listening to facts; they had to interact with it in a way that made sense in their own unique brains.

- Both methods have a process. What grazing charts and planning seminars do for the Savory method, weekly check-in conferences and daily routines do for the Montessori one. A common myth about Montessori is that the children are set loose to do whatever they want day after day, and while there is a grain of truth to that (I could certainly attempt to avoid math), I could never get more than four days without having to sit down with my teacher and show her the work I had -- or had not -- completed. The rest of that day would often be spent trying to do an entire week's worth of whatever I had ignored, and eventually, I learned the value of time management.

- Both methods, when used improperly, can create disastrous results. If cattle are rotated around with no regard to recovery time, you could very well wind up with paddocks that are far worse-off than when you started. Similarly, if you do what I mentioned above and just turn hoards of children loose, you can end up with a "Lord of the Flies" type of situation. In both cases, the name of the method can become synonymous with the damage it can create when not done correctly.

- Both methods tend to be judged by standards that don't necessarily apply. An example of this for the Savory method would be weeds. If someone trained to the conventional method sees that you have a thistle on your property, they may easily jump to the conclusion that you are not a responsible land manager, while in reality the long-term health of the soil is a far more effective way of getting rid of them than spraying. In Montessori, this could apply to the fact that some children progress more quickly in some areas than others. If you see one child becoming a fast reader and another one struggling, you may assume that the method does not work, when in fact the second child will come to it naturally, if a little later, on their own.

- In addition, many people believe that if certain standards are not in place, some things simply don't exist. In Montessori, there are no grades, so "how do you know that the children are learning?" Because, like Savory, there are indicators (bare soil/retention of information shown at weekly conferences) that professionals are trained to look for.

- Both methods are widely, vastly misunderstood. I already mentioned a few of the myths surrounding Montessori, but what's surprising are the number of myths that have zero grounds in reality. People claim that Montessori-taught children don't live in the "real world" (where janitors clean up after you and you exist in hour-long blocks of time?), that they don't read (our daily 45-minute silent reading time disagrees), that they are discouraged from being creative (???), and plenty more. The one that still gets me about Savory is the claim that "Holistic Management could never work here, because what works in Zimbabwe would never work in _____!" If you haven't done the reading or otherwise committed yourself to learning the method, chances are it's going to be a little confusing, and because of this,

- Both methods are greatly mistrusted. People who are used to doing the conventional way of things are made incredibly anxious by these two methods -- to the point that people who were not my parents, and therefore not responsible for me at all, were uncomfortable with the way I was being educated. I see the same with land managers, and in both cases, I'm overcome with the desire to educate. I find myself thinking, "If only you knew how much you were missing!"

My first day of school, somewhere around 3rd grade based on the crocs.

But this is what brings us back to that initial question. While I feel that I'm capable of understanding a great deal of the Savory method itself, I struggle with the concept of trying to explain it to someone who isn't familiar with the basic idea of holism, because holism is something that has been so deeply ingrained in me that anything else seems short-sighted. But on the bright side of this issue, once holism has been realized -- whether it's in farming or education or health -- it has the potential to positively affect everything else in our lives.